Denver: Betting on the future and seeing early returns

Tom Clark can cite the exact moment in 1997 when metro Denver’s economic leaders became convinced that a more comprehensive rail and bus network was critical to the region’s prosperity. They were talking to executives at Level 3 Communications about a potential relocation, but their prospects were balking. They were afraid that without transit, Denver’s potential workforce was effectively cut in half because of congestion on I-70, the main east-west interstate artery.

Tom Clark

“They were the catalytic piece of us deciding that we really had to get serious and get transit back on the ballot again,” said Clark, CEO of the Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation. “It was one of those a-ha moments in your life where you just go ‘Wow, this has real economic implications.’”

There were challenges in going to voters for transit funding at that stage, however. Denver International Airport, the area’s major infrastructure project of the 1990s, had been plagued with billion-dollar cost overruns and an automated baggage system that had to be scrapped. The public’s trust in local government’s ability to pull off large projects was at an all-time low, leading in part to the recent defeat of an ambitious but vaguely defined transit initiative called Guide The Ride.

Yet Denver leaders knew that, particularly in transportation terms, failing to plan meant planning to fail. And with potential employers beginning to look away, it became clear to leaders they needed a bold approach and a unified plan for a comprehensive expansion of their entire transportation network.

Bidding to put Denver on the “FasTrack”

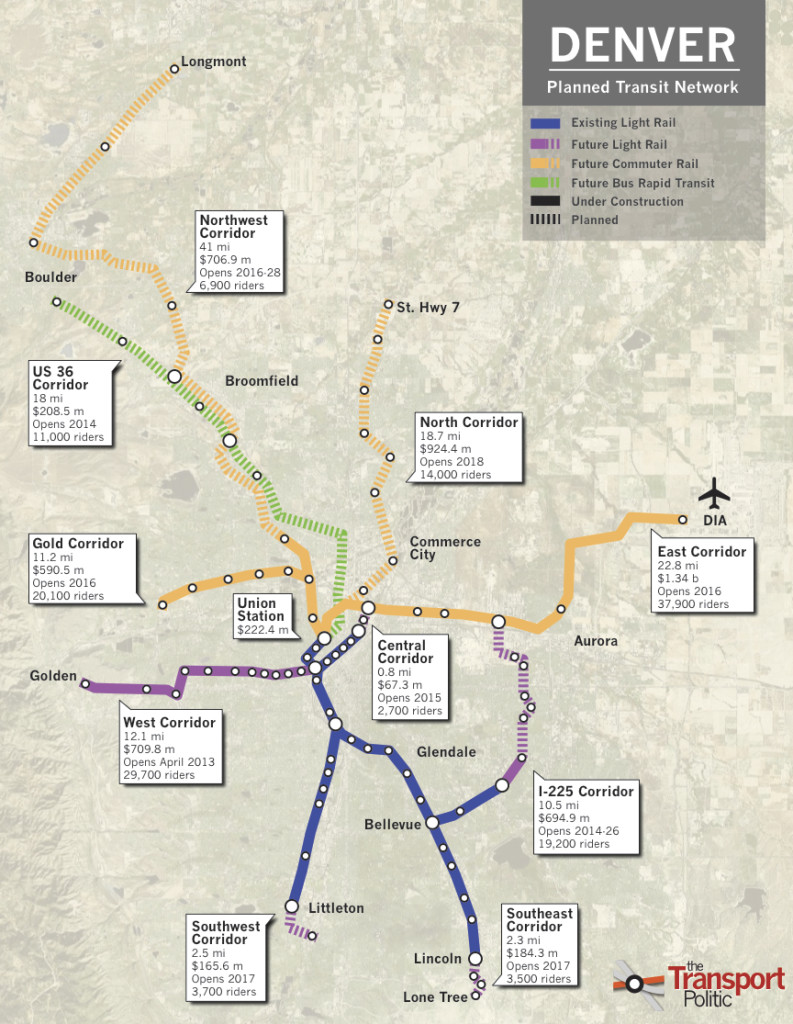

In the early 2000s, at the behest of the Chamber of Commerce and regional Metro Mayors Caucus, the Denver-area Regional Transportation District (RTD) began assembling an ambitious, detailed and comprehensive plan to invest in light rail, commuter rail, bus rapid-transit, expanded bus service and strategic highway improvements like managed lanes. Also included in the package were significant improvements to Union Station in downtown Denver to turn the beautiful, but underutilized, old building into a multi-modal transportation hub.

The resulting plan, dubbed “FasTracks”, totaled $4.7 billion, and would require increasing a regional sales tax from 0.6 cents to a full cent on each dollar of sales, along with federal grants, loans and private contributions.

While it was a stiff price tag, the comprehensive nature of the plan gave voters the sense that the plan could, indeed, provide alternatives to congestion as the region grew. This became especially critical after Denver was rated the third-most congested region in the country in the 2003 edition of the Texas Transportation Institute’s annual index, the year before FasTracks was put to a vote.

“We had a specific plan,” said Maria Garcia Berry, CEO of CRL Associates and a political consultant who worked in favor of FasTracks. “This was not pie in the sky. This was ‘Here’s what we’re going to do. And here’s how we’re going to do it.’

“Starting in June of 2004, we ran very simple ads on the radio right in the middle of rush hour,” Clark recalls. “We said, ‘Did you know that Metro Denver has the third-most congested highway system in the country? There’s a solution. FasTracks.’”

“We abandoned all myths about who votes for transit and who doesn’t and started from scratch and listened to the voter,” Berry continues. “What we heard, loud and clear, that the time was now and people wanted choices. People don’t believe anymore that there is a single solution. They don’t believe transit is the only way you solve congestion, but they want choices and options.”

In November 2004, the effort paid off and FasTracks was approved by a majority of voters, with 58 percent voting in favor.

Even before construction, plan begins to shape economic development

Today, pieces of the expanded system are beginning to become operational, with the western light-rail line from downtown through Lakewood the first to come online. But even prior to build-out, developers, landowners and business owners were already making investments along the new transit line. The most notable investment was the move of St. Anthony’s Hospital from a site it had outgrown elsewhere in Denver to a spot right next to a planned rail station.

Mayor Bob Murphy

“Lakewood is a city of nearly 150,000 that has never had its own hospital,” says Bob Murphy, Lakewood’s mayor. “They chose to locate there because of geography. They wanted to be on the west side, and they wanted to be at the center of a multi-hub transportation site. That has brought in 1,700 direct primary jobs, and 2,700 indirect primary jobs already in just over two years.”

Elsewhere along the line, the arrival of rail fueled demand for transit-oriented residential development. “Because of that narrow right-of-way and because of the residential characteristics of most of the line, it retains this streetcar line intimacy,” Murphy adds.

The centerpiece of the FasTracks project is Denver’s historic Union Station, where some $370 million is being invested to transform the 1914 Beaux Arts facility into a 21st-Century transit hub. Simultaneous projects include a hall for commuter rail lines, a 22-bay regional bus facility, a light rail station, a connecting shuttle and multiple public spaces in and around the historic structure. In turn, that investment has attracted private dollars, with developers building hotels, restaurants and more.

Denver Union Station rendering courtesy of the Denver Union Station Authority.

Union Station “is probably generating north of a billion dollars of private investment, which is pretty dramatic,” Berry said.

The line from Union Station to Denver International Airport, expected to begin operating in 2016, is a key component of the system and has already helped with luring potential employers, including a new regional office of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. “We consider ourselves to be an innovation hub, and if we didn’t get the Patent and Trademark Office expansion, it would have been a big hit against our brand,” said Clark. At the time of the selection by the USPTO, Denver officials estimated a $439 million economic impact on Colorado in the first five years after opening the new patent office.

“Everybody said one of the big reasons they voted for FasTracks was because it had the airport line,” noted Bill Sirois, RTD’s senior manager for TOD and planning coordination.

“The DIA [airport] line is a game changer,” Murphy observed.

Ensuring access for workers at all wage levels

As FasTracks projects continue to be built and transit-fueled projects proceed, there remains the possibility that rising property values may displace low-income families, taking them further from the transit that has the potential to improve their lives and lower their household costs.

Enter Mile High Connects, a nonprofit working with local partners to ensure improved transit benefits everyone, not just the more-affluent. “What we’re trying to do,” said Davian Gagne, MHC coordinator, “is make sure that communities don’t get pushed out … to the suburbs so far that they’re relying on their car to get their kids to childcare, to get them to work, or to get to a doctor’s appointment.”

To that end, two sister organizations, Enterprise Community Partners and the Urban Land Conservancy, have built a $15 million fund that can be used to acquire and preserve affordable housing that is near either current transit lines or proposed and future transit lines.

Ultimately, low-income individuals stand to benefit immensely from living a car-lite existence. “Could you imagine what it would be like for a family to have an extra $15,000 or $20,000 per year in their family’s budget because they’re using transit and not having to [buy and operate] cars so much?” she asks. “That makes a huge difference.”

In the meantime, job centers will become easier to reach as the system is built out. The I-225 light-rail line corridor, for example, will provide easy rail connections to three medical campuses, while the East airport line will carry not just travelers, but airport employees who will be relieved of the minimum $10 cost of parking at DIA.

Adapting to the effects of a down economy

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing.

Only four years into executing the FasTracks plan, the 2008 recession sent sales tax revenues plummeting, while demand for materials in emerging overseas markets, primarily China, drove costs sky-high. As a result, some FasTracks projects have been deferred as late as 2042, while others have sought public-private partnerships to make up for revenue gaps. Overall, costs now are some $2 billion more than originally estimated.

Despite obstacles, however, Denver’s bold investment in its economic future is already paying off, Clark said. “Up until three years ago, the number one place for 25-34 year olds to migrate to was Atlanta, and now it’s Denver.”

Bob Murphy agrees. “Major employers are looking for a few key factors. They’re looking for a highly educated workforce, a transportation infrastructure and recreational entertainment opportunities. … Finally, they’re looking for arts and culture, and we have that obviously in downtown Denver and Lakewood, so we feel like we’ve got it all.”

You can also nominate your “can-do” place (city, town, region, state) here for a future profile