Music City’s leaders “amped” about the future of their economy

Though not as large as Atlanta, its neighbor a few hours to the south, Nashville, TN struggles with some of the worst congestion in the Southeast and among the longest peak-hour travel times in the nation. With economic growth paving the way for continued population growth, Nashville leaders are trying to seize an opportunity to grow in a way that continues to enhance the region’s quality of life while attracting and retaining top-flight talent. At the same time they want to avoid the dysfunction that has plagued other Sunbelt metros

The economy is indeed booming in Nashville.

In 2012 the city led the nation in percentage job growth. With strong healthcare, entertainment, educational and tourism sectors, Nashville has become a draw for newcomers.

Today the city of Nashville—which extends to the borders of Davidson County and is governed as a consolidated unit—has a population of more than 600,000. The Middle Tennessee region numbers more than 1.8 million. And those numbers are projected to zoom higher in the near future. But that growth has a significant downside if not properly managed, and local leaders know that if they don’t make smart decisions today, they’ll kill the golden goose.

“The Nashville region is projected to grow by a million people between now and 2035,” says Nashville Mayor Karl Dean. “We have to prepare for it.“

However, Dean adds, this is going to require a more balanced approach than the plans of the past. The region has a robust network of freeways and with downtown infill redevelopment playing a significant role in the region’s economic vitality, ensuring continued mobility will require a different approach.

This is why Nashville is setting its sights on a rapid-transit corridor right through the heart of the city as the first piece of a broader regional system of higher capacity public transportation. Originally conceived as a light-rail line, “The Amp” is now planned as a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor, with dedicated lanes, traffic signals that give priority to buses, dedicated stations and streetscape improvements along the line’s service area.

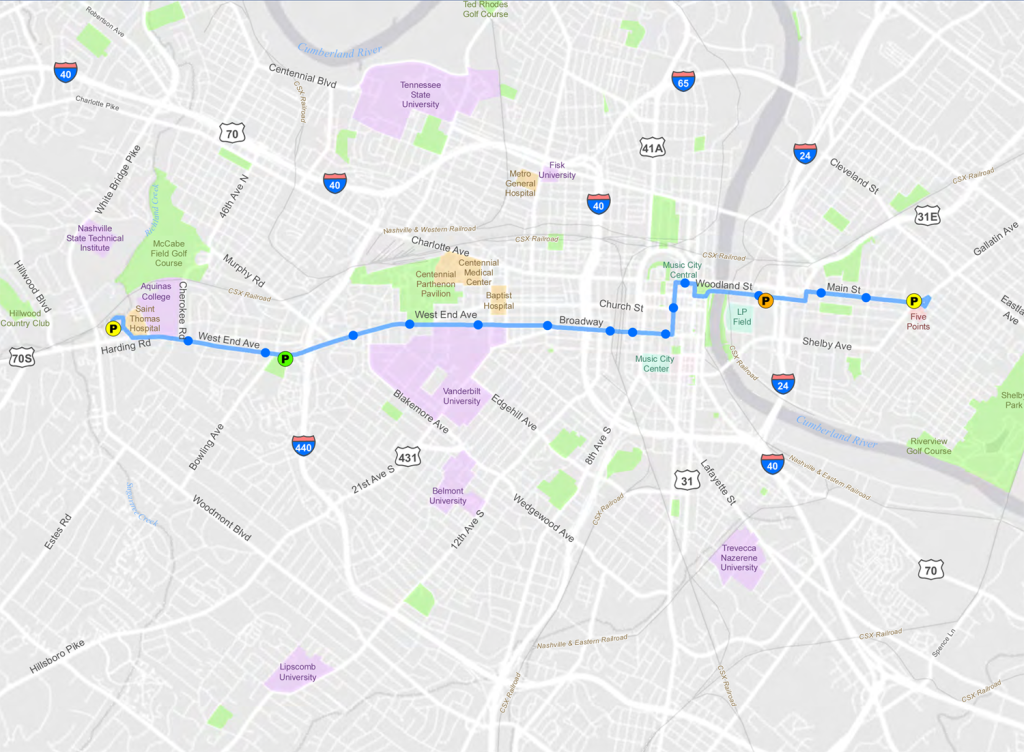

The Amp will run along the East/West spine of the city, along the Broadway/West End corridor, beginning in the Five Points area of East Nashville, crossing the Cumberland River and terminating next to St. Thomas Hospital in the West End. The route will connect passengers with numerous employers, including Vanderbilt University, several hospitals and many downtown hotels.

The Amp also will bolster tourism, a major economic pillar for the region, with more than 11 million tourists annually. The Amp will connect tourists to highly trafficked destinations, passing close to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, LP Field, Bridgestone Arena and the Ryman Auditorium, among others.

Bus rapid transit will operate differently from the Nashville Metropolitan Transit Authority’s standard bus lines. Fare collection will take place at station kiosks, rather than on board. The special vehicles will feature wide aisles, interior bike racks and free Wi-Fi. Stations will be spaced roughly a half-mile apart and will have real-time arrival/departure times, maps, weather protection, bike racks, and good lighting.

As of late 2013 the Amp was in the final design phase while officials sought to complete the $175 million required to build out the project, which includes federal, state, and local contributions, according to Michael Skipper, executive director of the Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization. Current ridership estimates call for 1.6 million passengers in 2016, increasing to 2.5 million annual passengers within five years.

The Amp will provide an opportunity to shape the city’s development pattern, Skipper notes, making it possible to move more people within the corridor without increasing traffic. He notes that around some stations, pedestrian-oriented streetscape improvements will extend a block into the surrounding neighborhood, making it easier to bike and walk safely. In addition, park-and-ride lots at each end of the line, as well as at the NFL Tennessee Titans’ LP Field will remove vehicles from the corridor.

Perhaps more importantly, the line promises reliability and predictability to those who will depend on it to get to work and to school.

“As a worker… if I have a dedicated line, I always know that I can count on it taking me 10 minutes, and I’m never going to be afraid of what the traffic looks like,” says Renata Soto, executive director of Conexíon Americas, which helps low- and moderate-income Latino families find economic opportunities and integrate into the community.

In addition, Soto predicted that better, more reliable transit would help working families access a broader variety of jobs. How? By transporting older children and easing the load on “mom’s taxi,” and by enabling families to look beyond their immediate neighborhoods for employment—for example, transporting workers to hospital jobs with upward mobility, instead of fast-food jobs with few opportunities to advance.

Diversifying the region’s transportation network is key for future economic success, according to Ed Cole, who leads a coalition of the region’s mayors as the executive director of the Transit Alliance.

“There’s no doubt that providing more transportation options is a key to our economic development,” he said, pointing out the generational shift in the mobility preferences of the types of talented employees that Nashville wants to retain — like Vanderbilt, Belmont, or other local university graduates — and also attract to the region.

“That generation is very interested in moving around efficiently, in being located in places where walking and biking are just as accessible as using the car, and transit is a big part of that. The chancellor of Vanderbilt University is very eloquent on this point: everything we can do to keep those graduates and to attract those kinds of citizens is a critical part of our economic development,” said Cole.

Remarkably, with many southern peers riven by city/suburb divides, the Nashville region is remarkably united behind its transportation initiatives, which also includes the Music City Star, a commuter rail line to Lebanon, TN, as well as express buses to other suburban communities.

“Transportation is a regional issue,” notes Ken Moore, mayor of neighboring Franklin and chair of the Middle Tennessee Mayors Caucus, a coalition of 40 mayors representing the entire area. “We live in one of the fastest growing cities in America. We see the projections. And we know what will happen if we continue to require people to drive their cars to get anywhere. Other options are critical for our long-term economic success.”

While Moore acknowledges that the initial phase of the Amp would not serve Franklin, he knows the importance of the first step to the region as a whole and is bullish on the future. “I think this is the beginning of bolder transit initiatives in our region to address the congestion on our highways and to improve people’s ability to get around.”

“People are naturally nervous about change,” Mayor Dean says. “But what I tell people is that change is coming no matter what we do. If we don’t do the Amp, you’re still going to see, by 2015, 20,000 more cars that will travel down the busiest section of West End. … What we have to do is be proactive and respond to the increased growth of the city and the increased number of vehicles, providing a transit solution. This is what we’re doing.”

Download an attractive, printable PDF of this story here, ideal for sharing

You can also nominate your “can-do” place (city, town, region, state) here for a future profile